In the 1940s and 50s, Viola Spolin was transforming how we understand learning through her pioneering work in improvisational theatre. Working with the Compass Players in Chicago, Spolin developed a systematic approach to theatre training that would influence generations of performers and educators.

Her seminal book, “Improvisation for the Theater,” published in 1963, remains a cornerstone text for theatre practitioners. Through her son Paul Sills, she founded The Second City, a comedy theatre that would become a proving ground for some of comedy’s most celebrated talents—Tina Fey, Steve Carell, Stephen Colbert, Bill Murray, John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, Amy Poehler…

Spolin’s technique centred on what she called “theatre games”—structured improvisational exercises designed to liberate performers from self-consciousness and mechanical acting. These weren’t just performance techniques, but carefully constructed learning experiences that challenged participants to be fully present, responsive, and creative.

“Through improvisation,” Spolin wrote, “the actor learns to trust his own spontaneity, to rely on his own discoveries, to be both the source and the critic of his own work.”

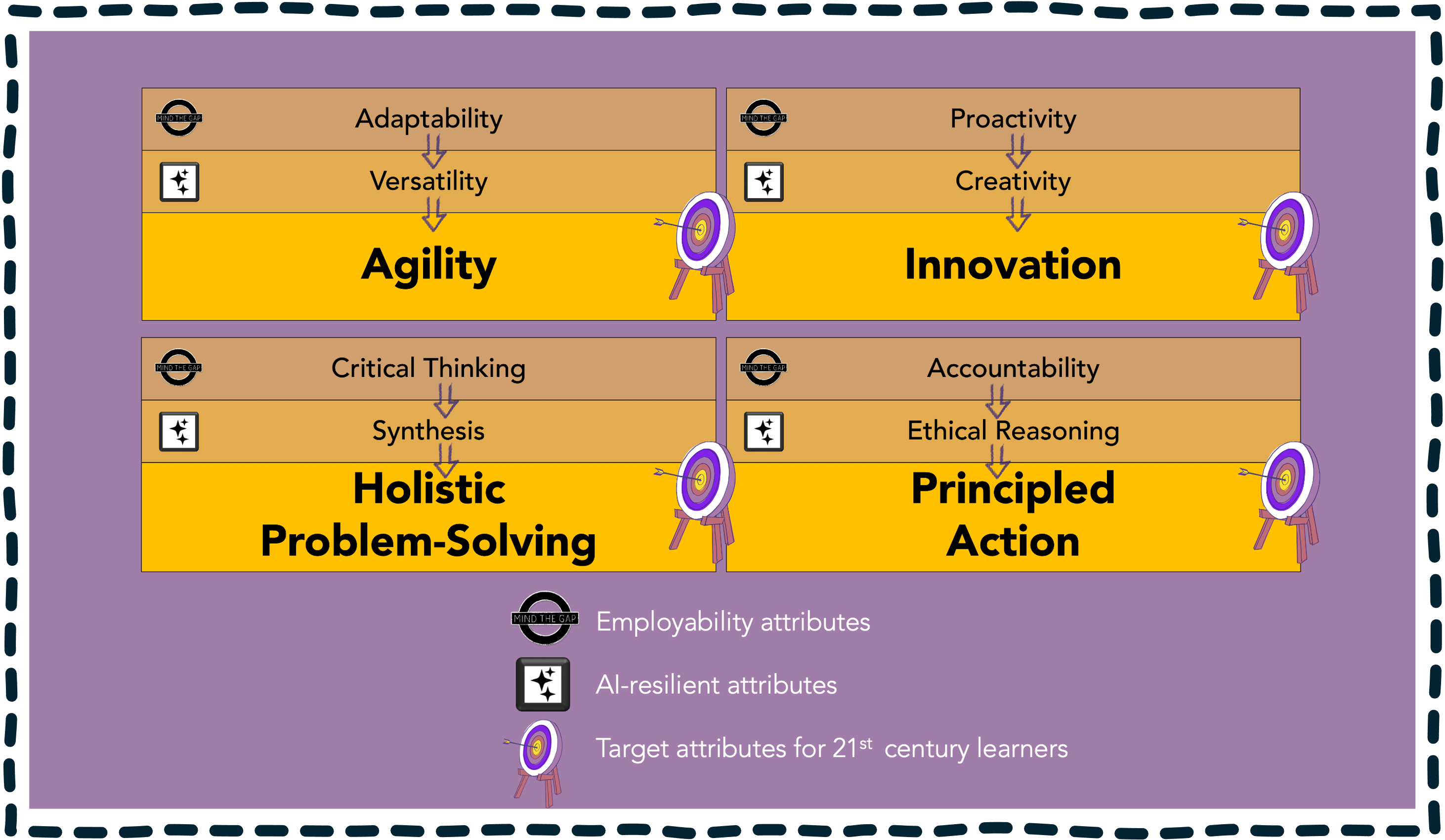

Four core attributes of employability

In our webinar The Art of Employability, Phil and I identified four core attributes essential for navigating today’s complex world: Agility, Innovation, Holistic Problem-Solving, and Principled Action.

Spolin’s championing of improvisation speaks directly to how we develop these essential human capabilities—spontaneity that helps us move quickly when things change, the confidence to rely on our own discoveries and turn them into innovative solutions, an ability to synthesise by connecting different perspectives, and the wisdom to be both ‘the source and the critic’ of our own efforts.

Just as Spolin argues that performance emerges from the ability to create and critique in the moment, learning transforms when we move beyond recitation to active, adaptive understanding.

Declarative knowledge—the facts, definitions, and information we can recite—becomes truly powerful only when transformed into functioning knowledge. Functioning knowledge is what happens when we move beyond simply storing information and learn to apply it in unpredictable, real-world contexts.

This transformation doesn’t occur through passive learning, but through active engagement—through improvisation, experimentation, and reflection. It’s about turning static information into a living, adaptable capability.

Case study: scenario-based learning in action

Turning information into ‘a living, adaptable capability’ was precisely the challenge IO-Sphere presented us. As a data analysis start-up, they’d discovered a critical gap: technically skilled analysts who understood the numbers but couldn’t breathe life into that knowledge within real workplace contexts.

Ding approached this by developing a multi-dimensional learning experience that went far beyond traditional training. We created an entire ecosystem of video-based learning resources, working with professional actors and a professional film crew to bring a fictional data analysis team to life. We filmed on location within IO-Sphere’s own premises, crafting intricate characters and scenarios that directly mirrored the real-world challenges their learners would encounter.

Our approach was holistic: we developed the characters, wrote detailed scripts, and produced professionally filmed narratives that introduced learners to a team of data analysts struggling with the very professional complexities they would likely face.

These video resources weren’t standalone content, but became the foundation for project briefs, learning activities, and immersive scenarios that surfaced the real turbulence of workplace dynamics—the conflicts, challenges, and collaborative complexities that traditional training typically sanitises.

Drawing from film and TV storytelling techniques, we crafted scenarios that demanded more than data analysis. Participants had to create value, tell compelling stories, navigate workplace dynamics, and influence decision-makers.

The actors’ experience

Advait Kottary, an actor who performed in the IO-Sphere project, captured Ding’s scenario-centred approach perfectly. “It’s almost like me describing to you how an apple would taste versus me just handing you an apple and asking you to experience it,” he noted.

What made our approach even more immersive was the deliberate blurring of boundaries. “Almost like you were a fly on the wall, seeing a situation unfold,” Kottary explained.

The real magic happened when Kottary was invited back by the IO-Sphere coaches to “break the fourth wall” and interact directly with the learners who had experienced these scenarios.

“I actually had the chance of interacting with several of the learners who underwent this bootcamp,” he shared, “and it was quite amazing to see how invested they were in the situation and the premise that had been created through these scripts.”

Why learning needs more improvisation

Spolin’s pioneering work in developing theatre games is more relevant than ever. As AI makes content easy to produce, effective learning experiences need to incorporate more improvisation in order to develop learners’ skills in adapting to change.

Incorporating scenarios and simulations into your learning and training is an effective way to begin developing the core attributes professionals need to be ready for the workplace.

Want to become a qualified learning designer?

We run a PGCert, PGDip and MA in Creative Teaching and Learning Design.